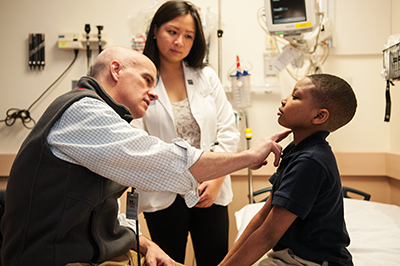

For more than two decades, most of which has been spent on the faculty of clinical partners Children’s National Health System (Children’s National) and GW’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS), Stephen J. Teach, M.D., M.P.H., has devoted himself to the health and well-being of children.

Since 1997, as professor of pediatrics and emergency medicine at SMHS, Teach has addressed chronic illnesses among the urban, and largely minority, child and adolescent populations of Washington, D.C. His leadership as director and principal investigator of IMPACT DC (Improving Pediatric Asthma Care in the District of Columbia), as well as his role as principal investigator for the NIH/NIAID-funded Inner City Asthma Consortium, has led to many awards and honors, including the Environmental Protection Agency National Environmental Leadership Award in Asthma Management. The renowned researcher, patient advocate, and author was recently appointed chair of the SMHS Department of Pediatrics in collaboration with Children’s National. As chair, Teach will focus on cultivating research initiatives, fostering faculty development, and preparing the next generation of pediatricians for clinical excellence.

Q: Who or what attracted you to the field of pediatrics?

A: I always felt drawn to the optimism and resilience of children. They are powerful motivators. It just felt right to care for them.

Q: What’s the biggest change or challenge you have seen in pediatrics?

A: The emergence of chronic disease in childhood; we have seen a generation of children survive previously fatal, early life challenges and become dependent, in many cases, on long-term therapies and medical technology. As we have become better at managing the complications of prematurity and of diseases like diabetes, cancer, sickle cell disease, asthma, and cystic fibrosis, patients with these disorders are living much longer lives, often with a much higher quality of life. Lots of work remains, however, to reduce their morbidity further, especially their dependence on medical technology.

Q: Why has asthma become such a big problem in the District of Columbia?

A: The District of Columbia and many similar urban environments constitute a perfect storm of adverse circumstances for diseases such as asthma. In the District, we have genetic and epigenetic factors contributing to very negative environmental factors, including poverty, poor housing, and inadequate access to primary care. Asthma is a good example of a condition for which we are now able to bring so many children under such brilliant control that they are able to fully participate in childhood activities, both academically and athletically. Today, there is very little that needs to restrict a child with asthma, whereas years ago that was not the case.

Q: Describe the relationship between Children’s National and SMHS.

A: It’s an evolving relationship that continues to be strengthened on many fronts. We are building upon that relationship through a host of collaborations centered on research and advocacy with initiatives such as the Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is funded by a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Institutes of Health. This was an award initially given as the base of a collaborative effort between Children’s National and GW, and it has been a great success. We have long taken pride in being the primary pediatric teaching institution for SMHS medical students. The beauty of the experience is that our students are able to see a range of inpatients and outpatients who suffer from a wide variety of common and rare disorders. I always like to point out to students that it’s by studying patients with rare disease and pathophysiology that you really understand how organs and systems are meant to work.

Q: What is the biggest challenge the next generation of pediatricians face?

A: I’ve become convinced that the biggest challenge young doctors will face is balancing their career aspirations with the reality of their personal financial circumstances. Young physicians are graduating from medical school with extraordinary amounts of debt, and I’m increasingly concerned that debt will drive both their career choices and their ultimate practice decisions. Unfortunately, I feel it deters them from pursuing primary care careers and forces them into specialty care and, more importantly, away from at-risk communities.

Q: What’s your vision for the department?

A: It’s pretty simple. My vision is to find and foster excellence in our medical students, trainees, and faculty through a very personal approach that stresses the unique interests and strengths of each individual.

"I always felt drawn to the optimism and resilience of children. They are powerful motivators. It just felt right to care for them."

Q: What are the strengths as you see them within the department, and how do you plan to leverage them?

A: This department is distinguished by a diversity of strengths in the multiple domains of modern medicine, specifically clinical care, research, education, and patient- and family-centered advocacy. More and more, we are recognizing the multidimensional nature of the health challenges in front of us. They require a very multidisciplinary and multipronged approach. For example, we make the most inroads against asthma morbidity by recognizing that we need to deliver care in a more efficient way, which includes using research to improve the next generation of care; advocating and influencing policy to ensure that children who need care are receiving it; and educating clinicians to optimally care for them.

Q: What part will research play?

A: Increasingly, we are conceptualizing research as the need to be able to create new knowledge and to translate our findings in a more concrete, meaningful, and patient-centered way to improve care and outcomes. We want to take the lessons that we learned from our research and become thought leaders. We want to be able to implement our findings within the context of our programs and initiatives that improve our patients’ lives.

Q: What areas of emphasis within the department have you identified to build upon?

A: We need to better integrate our somewhat siloed approaches toward research, education, advocacy, and clinical care to make them more synergistic. In our approach to a problem, such as premature birth, we need to address it as a medical, societal, and health policy problem. We need to ask ourselves: Are there systems in place to make sure that these moms are receiving optimal care to deliver the healthiest possible infants? [hr]