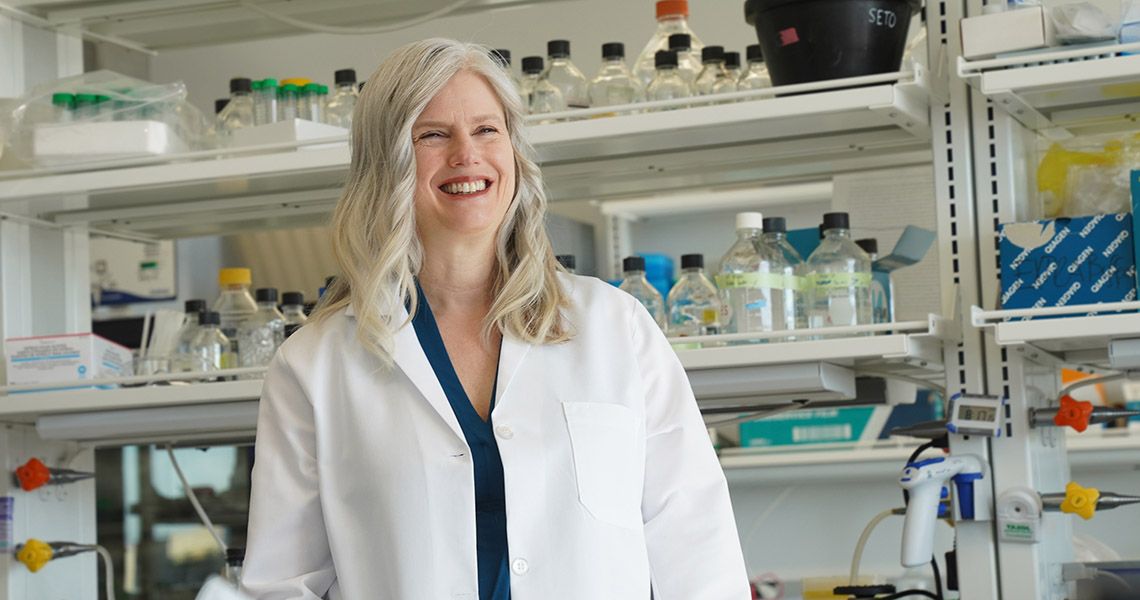

It’s been a whirlwind for Julie E. Bauman, MD, MPH, since she first arrived in Foggy Bottom in March 2022, to lead the George Washington University (GW) Cancer Center and serve as associate dean of cancer and professor of medicine at GW’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS). At the start of the fall 2022 semester Bauman presented the keynote address at the Class of 2026 White Coat Ceremony. In September she delivered the 11th Annual Frank N. Miller Lecture. By the end of October, Bauman was installed as the Dr. Cyrus Katzen Family Director of the George Washington University Cancer Center, only the second person to hold the title.

When the university opened the search for a new GW Cancer Center Director, Barbara L. Bass, MD, RESD ’86, professor of surgery, Walter A. Bloedorn Chair of Administrative Medicine, vice president for health affairs, dean of GW SMHS, and CEO of The GW Medical Faculty Associates, set a high standard. Candidates would need to able to move seamlessly between clinical care and basic, translational, and clinical research circles, have an active research portfolio, and possess leadership experience at a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Bauman’s academic credentials cleared those hurdles. While at the University of Arizona (UA) College of Medicine-Tucson, she served as professor of medicine, chief of hematology/oncology, and medical director of oncology services. She also was the deputy director of the UA Comprehensive Cancer Center and co-leader of its Clinical and Translational Oncology Program, connecting basic and clinical scientists to transform scientific discoveries into clinical applications. She is a nationally recognized leader in cancer therapeutics for both prevention and treatment, with a long track record of National Institutes of Health (NIH) team science funding, and her clinical research work earned her the prestigious NCI Clinical Investigator Team Leadership Award.

But for a city historically dogged by high cancer rates and troubling health care disparities, Bauman’s upbringing and her reverence for the doctor-patient relationship, made her stand out. Bauman was born in a small Alaskan Inuit village, when her father served in the Indian Health Service. She and her three sisters grew up across the desert Southwest, as their physician-parents worked to bring health care to the marginalized and underrepresented, particularly migrant worker communities.

“[Julie Bauman] brings a great vision for the city, our community, and she is committed to our ambition to eliminate cancer as a threat and often tragic for our nation and beyond,” said Bass. “There’s no question that we have a visionary leader who is already starting to transform and to invigorate our cancer center in a really exciting way to serve our patients and expand and build our scientific and clinical teams that will bring true excellence to our cancer center and the people we serve.”

Bauman’s mission is to grow the patient-centered, multidisciplinary oncology care center, with clinical research at its core, and complete the arc that delivers transdisciplinary research from the bench to the bedside. During her installation as the Katzen Family Director, she put a personal face on that goal.

Bauman recalled two former patients with advanced cancers. Each had already been treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, and had relapsed within months. Both were out of options.

“They both developed refractory oral cancer,” Bauman said, and they were treated in clinical trials that required the dissection and analysis of the molecular characteristics of their cancer.

The first patient, continued Bauman, participated in a clinical trial for the monoclonal antibodies ficlatuzumab and cetuximab, and has been in remission since 2018. The second, she said, was treated with immunotherapy, using a personalized cancer vaccine against the unique mutations in the patient’s individual cancer, a vaccine manufactured just in time. That patient also entered a remission.

“To me, on some days, they seem like miracles,” said Bauman. “The reality is those outcomes are rare, and they are built upon decades of painstakingly slow and often unsuccessful research. Only about 20% of people with cancer respond to immunotherapy, and that is exactly 80% too few, in my view.”

Here, Bauman discusses what drew her to GW, her plans for building on the momentum at the GW Cancer Center and bridging innovative research to equitable care.

Q: What attracted you to the GW Cancer Center position?

Julie Bauman: I’m a builder. I enjoy the interdependent challenges of vision-setting, strategy, and engagement to build toward a whole greater than the sum of its parts. I was drawn to GW as an organization that clearly values both scientific excellence and equity. Specifically, I was inspired by the scale of impact the GW Cancer Center could have for the D.C. community. Despite a relatively high-income base for the overall metro area, D.C. has notable disparities in poverty, insurance, education, environmental exposures, and other social determinants of health. This translates into some of the worst incidence rates and clinical outcomes for multiple cancers.

Q: What does being an NCI-designated cancer center mean?

Bauman: The hallmark of NCI designation, a P30 grant awarded by the National Cancer Institute, is when scientific discovery impacts people to improve outcomes. We want to become a cancer center that brings science to the bedside for prevention and treatment, delivers interdisciplinary care, is engaged with our diverse communities to understand their cancer priorities, and influences policy across health systems. Building a cancer center starts with the strategic imperative of evolving a patient-centered oncology service line. We need multidisciplinary teams that cut across the traditional academic departments and focus on the patient’s own journey, from diagnosis through treatment to survivorship. That navigated journey starts with prevention and early detection. If we build according to that vision, NCI designation would be a natural consequence.

What does that mean for the D.C. community? We know that patient outcomes are better at NCI-designated cancer centers. Why is that? Two things distinguish outcomes for patients treated in NCI-designated centers: team-based care and access to clinical research. Clinical trials bring not just novel therapeutics, surgical innovation, and radiation technologies with hope for better cancer outcomes, but also infrastructure and support. For patients, just being on a clinical trial, which results in high-level navigated experiences, may improve care. Both standard multidisciplinary oncology services and clinical research need to be built on the same navigation principles. One of my first initiatives is to build out navigation services from prevention through survivorship.

Q: What has been your top priority since arriving?

Bauman: The NCI describes six essential characteristics of the cancer center; one of these is transdisciplinary collaboration. A cancer center brings together investigators on campus and within the community to drive transdisciplinary collaboration that reaches the bedside. Building clinical services and clinical research allows the full arc of discovery to touch people.

The first GW Cancer Center Director, Edward Sotomayor, MD, did a wonderful job building what I would describe as the “basic science half” of the cancer center: research programs in cancer biology, immunology/immunotherapy, cancer engineering, and population health that are the engine of discovery. I am continually learning about the cancer-focused, peer-reviewed research grants held by GW Cancer Center members; to my delight, collective funding almost reaches the threshold needed to submit an NCI grant application. However, without a robust clinical research infrastructure, where at least 10% of patients are enrolling in clinical trials, an application can’t succeed.

I talk about building the “clinical half” of the cancer center and weaving it all together. Building clinical science will enhance the impact of the research programs, driving our scientific discoveries at GW to our patients to enhance their outcomes. Rigorous clinical investigation also brings discoveries made in the real world back to the laboratory. It’s important to emphasize that building exceptional clinical science does not sacrifice basic science. Rather, they elevate one another.

Q: What areas would you most like to develop in GW’s clinical research scope?

Bauman: Among the areas I have in mind, where I think we can become national leaders, are cancer prevention and precision immunotherapy. The latter is the idea of developing treatment strategies that harness the body’s natural immune system to eradicate cancer.

Under that umbrella, as an example, we have a remarkable cellular therapy program led by Catherine Bollard, MD [associate center director for translational research and innovation, GW Cancer Center, and professor of pediatrics at Children’s National Hospital], where human immune cells are engineered to attack cancer. One of my strategic initiatives is to build the adult counterpart to her pediatric program. We started with the construction of a GMP (good manufacturing practice) cell facility in Ross Hall. This will enable us to design and manufacture living cellular therapies that can be administered to humans, a capability that will differentiate us regionally and nationally.

Q: What is precision therapy? Is it the next chapter in cancer treatment?

Bauman: Cancer is a wily enemy from a therapeutic standpoint. It’s made from cells that are more than 99% the same as our body’s regular cells. Precision therapy is understanding the patient’s tumor, its genetic makeup, and how it hides from the immune system. It exploits what’s different between the cancer and the person. How do we administer therapies that exploit the vulnerabilities of that less than 1% in cancer cells, while not harming the normal cells? That’s been the challenge.

Think about the growth and development of therapeutics for cancer treatment over time. We started with cytotoxic chemotherapy, which I liken to a hammer or cannon fire; it’s administered as a heavy-duty, indiscriminate toxin. Chemotherapy kills fast-growing cells, and some cancers will respond incredibly well to it, but it also kills innocent bystander cells. Subsequently, we’ve seen the advent of targeted therapies, which ushered in the era of precision oncology. This involves identifying and targeting a DNA abnormality present only in cancer, such as the BCR-ABL gene in chronic myelogenous leukemia, or the EGFR mutation in metastatic lung cancer.

Here, drugs block that abnormal pathway in a targeted fashion. Targeted therapy kills cancer cells more readily than normal cells, but it’s still a matter of degree. Although cancer cells are more reliant on these pathways, normal cells still have some dependency on them, so there are still side effects.

Some work that I’m engaged in is called the “personalized cancer vaccine.” In this form of precision immunotherapy, we analyze that less-than-1% difference in the genetic makeup of the cancer cell versus the normal cell. The mRNA corresponding to up to 20 of these mutations is loaded onto a personalized cancer vaccine, which carries that intelligence to the immune system, explaining precisely what is different about the cancer cell and flagging it for destruction. This, in my view, is the exciting future of cancer therapeutics.

Q: What is your vision for clinical research in cancer prevention?

Bauman: Thomas Adams, an English clergyman born in 1612, spoke on the importance of prevention, saying, “Prevention is so much better than healing, because it saves the labor of being sick.” As an oncologist, I see firsthand the suffering associated with cancer, even when a cure is possible. Up to half of all cancers are preventable, thanks to interventions such as HPV vaccination, colonoscopy, or tobacco cessation. I am also interested in the reduction of cancers caused by factors outside the individual’s control, such as permissive tobacco policy, environmental pollution, food deserts, and pestilence — risks disproportionately borne by the poor and dispossessed. Cancer prevention requires intervention at both the individual and societal levels.

From a clinical research standpoint, I am immersed in so-called “green chemoprevention,” the use of whole plants or their simple extracts to prevent cancer. I just completed a clinical trial showing that a nutraceutical composed of broccoli seed and sprout extracts increased the detoxification of tobacco carcinogens, including benzene, in healthy smokers. I recently initiated the follow-up study, evaluating whether this effect is sustained over a 3-month period against placebo, a gold standard for moving this green chemoprevention strategy into a large, randomized cancer prevention trial. Interestingly, a similar nutraceutical increased the detoxification of air pollutants in residents of southern China. Green chemoprevention, which can build on local foods and customs, raises the promise of global mitigation of individual and societal-level cancer risks.